|

Potato Inca's Food

As Other Staples Soar, Potatoes Break New Ground.

Hiram Bingham, the American explorer who found the

ruins of Machu Picchu in 1911, wrote:

To the Incas the art of agriculture was of

supreme interest. They carried it to a remarkable extreme, attaching

more importance to it than we do to-day. They not only developed many

different plants for food and medicinal purposes, but they understood

thoroughly the cultivation of the soil, the art of proper drainage,

correct methods of irrigation, and soil conservation by means of

terraces constructed at great expense. Most of the agricultural fields

in the Peruvian Andes are not natural. The soil has been assembled, put

in place artificially, and still remains fertile after centuries of use.

The Incas learned the importance of

fertilizers to keep the soil rich and fruitful. They had discovered the

value of the guano found on the bird-islands that lie off the coast of

Peru, setting aside various of these islands for the benefit of

different provinces. No one was allowed to visit the islands during the

breeding season. Although hundreds of thousands of fish-eating birds

inhabit the islands, the Incas punished by death anyone killing a single

guano-producing bird.

They depended on terrace agriculture. It is

seen in its most conspicuous form on steep slopes. Terraces are found in

many other countries, notably in east Asia and the Philippines, but it

is very doubtful whether any equal those constructed by the Incas. In

Peru the artificial reconstruction of the surface soil was not limited

to slopes, but was also undertaken in large areas of reclaimed land in

valley bottoms. They even narrowed and straightened the courses of the

rivers, filled in the land behind strong walls and topped off the work

with a surface layer of fine soil.

The system of terrace agriculture which they

developed consists roughly of three parts, the retaining wall and two

distinct layers of earth that fill the space behind the wall. The

underlying stratum, an artificial sub-soil, is composed of coarse stones

and clay to a thickness that depends upon the height of the retaining

wall. This stratum was covered by a layer of rich soil two or three feet

deep.

Fortunately for the Incas the soils in the

terraced districts are tenacious and not readily eroded. A few sods or a

small ridge of earth will hold in check a stream of water, thus greatly

facilitating the irrigation of the terraces. In places, large stones

deeply grooved lengthwise served as spouts to carry the water out from a

terrace wall thus avoiding the danger of erosion or undermining.

Mr. O. F. Cook, the distinguished authority

on tropical agriculture who was the botanist on one of my Peruvian

expeditions, tells me that the Incas and their predecessors domesticated

more kinds of food and medicinal plants than any other people in the

world.

They found a small plant growing in the high

Andes, with a tuberous root about the size of a small pea. It proved to

be edible and from it, in the course of the centuries, they finally

developed a dozen varieties of what we call the "Irish" or white potato,

suitable for cultivation at elevations varying from sea level to

fourteen thousand feet above it. After the Spanish Conquest of Peru, it

took Europeans nearly three centuries to appreciate the staple food of

the Incas. In fact, had it nit been for famines in France and Ireland it

is hard to say when the Peruvian potato would have been accepted as part

of their daily ration.

The skill and ingenuity of the Inca

agriculturists was shown not only in the breeding and raising of many

kinds of potatoes, but also in the very many varieties of maize or

Indian corn, suitable for cultivation at varying elevations, which they

developed. No one knows exactly the plant from which maize was

originally derived. There is no doubt, however, that the Incas had more

varieties of maize, a whole series that were unlike any that are known

from Central America or Mexico, and had gone to a far greater extreme in

developing them than did the Mayas.

An Inca food plant almost unknown to

Europeans is canihua, a kind of pig weed. It is harvested in

April, the stalks are dried and placed on a large blanket laid on the

ground as a threshing floor. The blanket serves to prevent the small

greyish seeds from escaping when the flail is applied.

Another unfamiliar food plant, also a

species of pig weed, is called quinoa. Growing readily on the

slopes of the high Andes at an elevation as great as most of our Rocky

Mountains it manages to attain a height of three or four feet and

produces abundant crops. The seeds are cooked like a cereal and are very

palatable.

At lower elevations in the Andes the Incas

developed another series of root crops, most of which are still

unfamiliar to us, but one, the sweet potato, has achieved world-wide

popularity.

In addition to discovering and developing

useful food plants, the Incas also were the first to learn the

advantages of certain medicinal herbs, particularly quinine, long known

as a specific in the cure of malaria. They also discovered the specific

effects of cocaine, which is extracted from coca leaves, but only

allowed it to be used by those engaged in such strenuous activities as

the marathons of their post runners. Judging by the "medicines" sold by

the Indian "druggists" who display their wares in the market places of

the mountain towns, the ancient remedies included such minerals as

sulphur, such vegetables as the seeds, roots, and dried leaves of

tropical jungle plants, and such animals as star-fish!

Source:

‘Lost City of the Incas, The Story of Machu

Picchu and its Builders’ by Hiram Bingham

The American explorer who found the ruins of Machu Picchu in 1911.

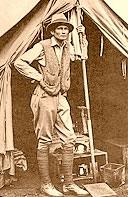

Hiram Bingham at Machu Picchu

The inspiration for Indiana Jones?

|