|

Hiram Bingham, the American explorer who found the

ruins of Machu Picchu in 1911, wrote:

Inca bronze has been found to be remarkably pure, aside from very small

quantities of sulphur. The proportion of copper in Inca bronze varies

from 86% in some articles to 97% in others. Some archaeologists have

taken the position that since the greatest quantity of tin is usually

found in those bronzes that would seen to require it least, the presence

of tin in Inca bronzes should be regarded as accidental. This hypotheses

has been carefully considered by the experts of the largest copper

companies now known that during World War II enormous quantities of tin

were recovered from Bolivian mines where our manufactures were delighted

to secure supplies to take the place of those that came from the Straits

Settlements before the Japanese occupation. It is also well known that

enormous deposits of copper are found in Peru and in Chile but not in

combination with tin.

My friend Professor Charles H. Matthewson of Yale University, was the

first modern metallurgist to make an exhaustive study of Inca bronzes.

He discovered that the percentage of tin contained in Inca bronzes was

not governed by the uses for which they requirements of the ancient

methods of manufacture. Everything that we know about Inca metallurgy is

based on Professor Matthewson’s report.

The Incas learned the interesting fact that bronze containing a high

percentage of tin yields the best impression in casting because during

the process of solidifying it expands more than bronze having a low tin

content. Hence the more delicate or ornamental pieces contain the

highest percentage of tin. Artistic details were thus more strikingly

brought out in the finished product. Of course, had the Incas possessed

steel graving tools the case would have been different. However, the

Inca metallurgists learned that the operation of casting small delicate

objects is facilitated when there is about ten percent of tin in the

mixture. Such alloys retain their initial heat longer and so remain

longer in a fluid condition. Since small objects tend to cool rapidly

this knowledge was particularly useful in the manufacture of ornamental

shawl-pins and ear spoons and accounts for the higher percentage of tin

the Incas used in making them.

|

Treasured Found. Peru Gets Pre-Inca Gold Headdress

Returned.

Looted Peru Moche Headdress Recovered in London. |

Since these early metallurgists were unfamiliar with modern methods of

heat treatment they were compelled to sacrifice the extra hardness and

strength obtainable in casting axes and chisels by increasing the tin

content in them. Such implements had to be frequently hammered and

annealed. Since cold-working had to be depended upon to produce the

final hardness of such objects, more than one heating was needed in

forging the blades and this process necessitated a low tin content.

Necessarily they employed a formula for combined cooper and tin which

has impressed archaeologists only familiar with the chemical analysis of

Inca bronzes, as being that which is unsuited for axes, chisels and

large knives. It was only after a metallographic study of Inca bronzes,

involving the mutilation of the pieces examined that Professor

Matthewson learned the structure of such objects, the methods of their

manufacture and the reasons for the variation that has been found to

exist. The Inca metallurgists cast their bronze knives generally in one

piece and then cold-worked them.

Such reheating as took place was solely for the purpose of softening the

metal to facilitate cold-working, which was probably done at less than

red heat. Some Inca bronzes are found to have been repeatedly hammered

and reheated. This hammering might have been done with the stone tools

with which the Incas were familiar.

The knife blades appear to have been worked and hammered so as to extend

the metal more or less uniformly in several directions. Chisels and

axes, on the other hand, were cast practically in the shape finally

desired.

The Inca metallurgists were sufficiently ingenious to use more than one

variety of bronze in the construction of an inverted “T” . If it was

desired to ornament the of the handle with a llama’s head or attractive

bird, the ornament would be made of bronze with a content of tin. The

metal of the blade and the lower part of the handle on the other hand

was of bronze of lower tin content because the blades had to be

cold-worked.

The ornamental part of the knife handle was actually cast around the

shank of the knife handle was actually cast around the shank of the

knife after it had been completed. The Inca artisan, anxious to make a

good serviceable knife and at the same time make it attractive, had

learned over the centuries to take infinite pains in doing it. If he

wished to make a hole in the end of a knife or shawl-pin, he did it in

the process of casting because he lacked steel tools for drilling it.

In making bronze bolas which could be used in capturing a flying parrot

or many-hued macaw, he cast the ball with a pin already in so that the

cord connecting the two parts of the bolas could be securely fastened

without interfering with the smooth flight of the missile. The pin was

not set into the bolas but was cast in place. It must have been a great

sight to see an Inca hunter bring down a flying macaw with a skillful

swing of the little bronze bolas, discharging them at just the right

moment to entangle its wings and legs without damaging the beautiful

captive.

Some axe blades bear evidence that they were used upon stone. Their

structure shows severe damage of a character which could only result

from very hard usage. They were probably used in cutting square holes in

ashlars and in making sharp inside corners. It is difficult to conceive

of any stone tools that could have been used successfully for this

purpose. Some writers have assumed that the Incas use bronze implements

to a large extent in finishing their best stone work. It seems to me,

however, that even their best bronze was too soft to last long in such

activities. It is not likely that it was often so employed. Experiments

made in our National Museum have demonstrated that patience,

perseverance, elbow grease and fine sand will enable stone tools of

various shapes to work miracles in dressing and polishing both granite

and andesite.

However, it is reasonably certain that the Inca builders used powerful

little bronze crow-bars to get those ashlars in place which were too

heavy to be lifted by hand. Called champis, these bars were sufficiently

strong to be used in adjusting blocks of stone weighing ten or twenty

tons. In a tensile test, made under the direction of Professor

Matthewson, an old Inca champi of poor quality showed an ultimate

strength of 28,000 pounds to the square inch. We found by experiment

with a new bronze crow-bar of the same Inca metallurgists, it had still

greater strength. The Incas could have used their little crow-bars for

prying into place granite blocks weighing twenty tons without damaging

the champis.

Inca bronze included not only such tools as axes, knives, chisels, and

crow-bars but also such domestic utensils as tweezers, shawl=pins, and

large bracelets, spangles and bells. They even made ear spoons, the ends

of whose handles were often decorated with figures of humming birds.

Perhaps the commonest bronze articles made by the Incas were shawl-pins.

Early drawings made by the Spanish conquerors show these pins were

always used for fastening the front of the shoulder covering. This

custom is still common in the Andes and I have noticed in many cases the

head of the shawl-pins is made like a spoon. The Incas do not appear to

have been familiar with spoons. The heads of their shawl-pins, which

vary in length from three inches to nine inches, are very thin so that

the edges were fairly sharp and appear to have been used for cutting

purposes. As the Inca women were frequently occupied in spinning yarn by

means of a hand spindle, or in weaving textiles, they would have found

such little knives very useful and handy.

They made bronze mirrors similar to those found in ancient Egyptian

tombs. They even succeeded in making a concave bronze mirror which, when

polished the rays of the sun to be sufficiently concentrated on a bit of

cotton as to set it on fire. One cannot help being impressed with the

great skill of the Inca metallurgists and wondering how long it took

them to learn this art.

They also made bronze bodkins or large needles with eyes sufficiently

large to permit them to carry a fairly stout cord. Sometimes these eyes

were made by flattening the head to a narrow strip, drawing this under,

laying it against the shaft of the bodkin and hammering enough of the

sides onto it to secure it. This process would readily have been

accomplished by the use of one of the little braziers.

They made little bronze tweezers intended to take the place of the

modern razor. Highland Indians seldom have any hair on their faces. The

Incas were probably anxious to remove any stray hairs by means of

tweezers was even known amongst the tribes of Micronesia in the Gilbert

Islands before it was thought of in New York or Paris. It is evident to

the observer of manners and customs that the desire for beauty parlors

is nothing new under the sun.

Source:

‘Lost City of the Incas, The Story of Machu

Picchu and its Builders’ by Hiram Bingham

The American explorer who found the ruins of Machu Picchu in 1911.

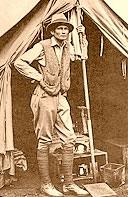

Hiram Bingham at Machu Picchu

The inspiration for Indiana Jones?

|