Quechua: the Inca Language

Hiram Bingham, the American explorer who found the

ruins of Machu Picchu in 1911, wrote:

Some American archaeologists are prone to

shorten the length of time during which the civilization of the Incas

was developing. Because the Mayas of Central America used hieroglyphics

and invented a calendar it is easy to grant them a couple of thousand

years, while the Incas are limited to a few hundred. Technically they

are right, if one chooses to restrict the use of the word Inca to the

few centuries when the rulers were actually called Incas. But if one

uses the term Inca to characterize that remarkable civilization

discovered by the Spaniards in the sixteenth century, with its advanced

agriculture, its magnificent engineering works and its success over

centuries in producing from an exceedingly wild ancestor two such

distinct domestic and pure-bred animals as the llama and alpaca, it

becomes evident that the period covered by the growth of this ancient

Peruvian civilization certainly must have lasted for several thousand

years.

This theory is also confirmed by the many

varieties of both potatoes and corn found in Inca land, and also by the

fact that the guinea pigs (cuyes) which they domesticated and bred are

as widely different in color and in coat as are the cats of the

Mediterranean region which are known to be of extremely ancient lineage.

Unfortunately

the ancient Peruvians never developed any

form of script or picture writing. It is

indeed a great pity that the Incas never had

the opportunity, as did the Greeks and

Romans, to come in contact with a people

like the Phoenicians who were clever enough

to invent an alphabet.

The language of

the Incas was the Quichua or

Quechua tongue. Originally it was used

only in a small area around Cuzco where the

Inca dynasty originated, possibly in the

tenth or eleventh century. During the next

five hundred years, when the Incas succeeded

in subduing the native races as far north as

Ecuador and as far south as Argentina, they

carried the Quechua language with them and

insisted in its being learned by the

conquered peoples so that it had a wide

distribution by the end of the sixteenth

century.

Today (1911) the

total population of Peru is about seven

million. A recent census reports that two

and one-half million speak Quechua and

two-thirds of these speak no other

languages. Although there are many different

languages spoken by small forest tribes in

the Amazon basin, there are only two

aboriginal languages numerically important

in the Andes, Quechua and Aymara. In the

region around Lake Titicaca and in northern

Bolivia the Indians speak Aymara which has a

phonetic system and grammar similar to

Quechua. Neither of these languages is

related in any way to those of eastern South

America nor to any outside the continent.

Philological experts are of the opinion that

nearly five million people in South America

still speak the language of the Incas.

Obviously it is by far the most important

native language in either North or South

America. That this phonetic system is so

widespread is in itself a remarkable tribute

to the extraordinary people who were so

successful in breeding animals and plans.

There are few

words in Quechua to denote abstract

qualities. On the other hand, the people

obviously were not militaristic for the word

meaning "soldier" also means "enemy." The

extent of the empire is emphasized by the

fact that the word for "foreigner" means

"those belonging to a city a great distance

off." The importance of agriculture is

strikingly demonstrated by the fact that in

Quechua there is but one word for "work" or

"cultivate." Apparently cultivating the soil

was the only thing which rated as work.

An interesting

commentary on the habits of the ancient

people and a sidelight on their manners and

customs is the abundance of expressions in

Quechua for all stages of drunkenness. One

of their principal activities was the

manufacture of beer or chicha. It was

brewed from sprouted corn which served the

Andean people as an upper mill-stone or

pestle. The Indians of Mexico and Central

America in grinding their corn use a miller,

pushed back and forth on a slab. This is

more fatiguing and requires more effort than

the rocking stone invented in the Andes. The

fact that the most common necessity of the

household, a means of grinding corn, was not

the same with the Incas as with the Mayas,

points to the long period of separate

evolution.

The Incas domesticated at least three

varieties of dogs but there is no evidence that, like the Polynesians,

they used any of them as an article of food.

Source:

Lost City of the Incas, The Story of Machu

Picchu and its Builders by Hiram Bingham

The American explorer who found the ruins of Machu Picchu in 1911.

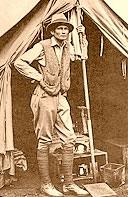

Hiram Bingham at Machu Picchu

The inspiration for Indiana Jones?

Glossary of Quechua Words:

|

Quechua |

Translation |

|

Acllacuna |

Chosen Women |

|

Alpaca |

Domestic camel animal |

|

Apachita |

Sacred offering, cairn |

|

Aquilla |

Golden goblet |

|

Ayllu |

Social division, 'clan' |

|

Canca |

Sacred bread |

|

Charqui |

Dried, 'jerked' meat |

|

Chasqui |

Relay runner |

|

Chicha |

Fermented beverage, corn

beer |

|

Chullpa |

Burial vault or tower |

|

Chuņu |

Desiccated potatoes |

|

Coca |

Narcotic plant |

|

Collahuaya |

Class of native

physicians |

|

Coya |

Queen |

|

Curaca |

Queen |

|

Guaman |

Province, political

division |

|

Guanaco |

Wild camel animal |

|

Guano |

Bird or bat excrement |

|

Hauasipascuna |

'Left-out Girls' |

|

Hihuaya |

A form of punishment |

|

Huaca |

Sacred place,

archaeological site |

|

Huaco |

Archaeological site |

|

Huaquero |

Native digger, treasure

hunter |

|

Huahuqui |

Supernatural Guardian,

brother |

|

Huayara |

Fertility festival |

|

Ichu |

Coarse grass |

|

Inca |

Inca |

|

Llama |

Domesticated camel

animal |

|

Llama |

Fillet, head-band |

|

Macanamaqna |

War club |

|

Mamacuna |

Mother Superior |

|

Mita |

Tax-service |

|

Mitima(es) |

Compulsory colonist,

settler |

|

Napa |

White (albino) llama |

|

Oca |

Cultivated tuber

(oxalis) |

|

Pachaca |

Political unit of 100

families |

|

Pampa |

Low-level treeless or

grassy plain |

|

Pirca |

Masonry of undressed

field stones |

|

Pucara |

Fortress |

|

Puna |

High-level grassy plan |

|

Puric |

Able adult man, head of

household |

|

Quechua |

Quechua |

|

Quero |

Wooden goblet |

|

Quinua |

Cultivated amaranth (Chenopodium) |

|

Quipu |

Knotted record |

|

Quipucamayoc |

Knot-record keeper |

|

Saya |

Section of a province |

|

Sinchi |

Chief, leader |

|

Situa |

Curative festival |

|

Suyu |

Quarter of empire |

|

Taclla |

Spade or foot-plough |

|

Tambo |

Inn, barracks |

|

Tocco |

Cave mouth, window |

|

Topo |

Shawl pin; standard of

measurement |

|

Totora |

Reed, rushes |

|

Vicuņa |

Fine-haired wild camel

animal |

|

Villac Umu |

High Priest |

|

Villca |

A narcotic (Piptadenia) |

|

Yacarca |

Soothsayer, diviner |

|

Yancuna |

Class of servants |

Reference: ' The Ancient Civilizations of

Peru' by J. Alden Mason, 1957

|

Online Book Shopping

|

|

|

She-Calf and Other Quechua Folk Tales (English and Spanish Edition)

by Johnny Payne

Textbook (Paperback - 1 ED)

These fables from highland Peru, presented in both Quechua and English,

capture a rich oral tradition and illustrate many universal human

themes. This bilingual edition, the first collection of stories from the Cusco region to be published in English, captures a rich but fast disappearing oral tradition. The ethnographic introduction, a poignant re-creation of what living and working with Quechua speakers reveals to a perceptive and appreciative outsider, is conversational, witty, and memorable for its insights.

Biography

Johnny Payne, a novelist, playwright, and translator, is a specialist in

comparative literature. He directs the creative writing program at

Florida Atlantic University. For three years he headed a summer

institute in Quechua history and literature in Cusco, Peru. |

|