The Quipu, the Pre-Inca Data Structure

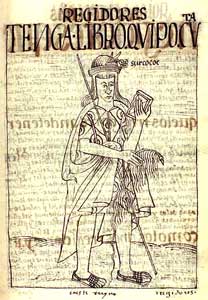

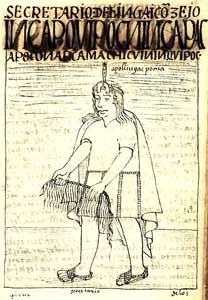

Above center: An illustration from 1615 showing

the Fibonacci series 1, 2, 3, 5.

Quipu's ancient knots,

Pre-Inca data preserved,

Threads of knowledge bind.

Cultural memory thrives,

Whispers from the past survive. |

|

The Quipu is a system

of knotted cords used by the Incas and its

predecessor societies in the Andean region to store massive

amounts of information important to their culture and

civilization.

The colors of the cords, the way

the cords are connected together, the relative placement of the

cords, the spaces between the cords, the types of knots on the

individual cords, and the relative placement of the knots are

all part of the logical-numerical recording. For example,

a yellow strand might represent gold or maize; or on a

population quipu the first set of strands represented men, the

second set women, and the third set children. Weapons such as

spears, arrows, or bows were similarly designated.

The combination

of fiber types, dye colors, and intricate knotting could be a

novel form of written language, according to Harvard

anthropologist Gary Urton. He claims that the quipus contain a

seven-bit binary code capable of conveying more than 1,500

separate units of information. The combination

of fiber types, dye colors, and intricate knotting could be a

novel form of written language, according to Harvard

anthropologist Gary Urton. He claims that the quipus contain a

seven-bit binary code capable of conveying more than 1,500

separate units of information.

Quipus were knotted ropes using a

positional decimal system. A knot in a row farthest from the

main strand represented one, next farthest ten, etc. The absence

of knots on a cord implied zero.

Quipucamayocs, the

accountants of the Inca Empire (called Tahuantinsuyu in old

spelling Quechua) created and deciphered the quipu knots.

Quipucamayocs were capable of performing simple mathematical

calculations such as adding, subtracting, multiplying, and

dividing information for the indigenous people.

In the absence of written records

the quipus served as a means of recording history and passed on

to the next generation, which used them as reminders of stories.

An thus these primitive computers - quipus - had knotted in

their memory banks the information which tied together the Inca

empire.

Hiram Bingham, the American explorer who

found the ruins of Machu Picchu in 1911, wrote:

"The

Incas had never acquired the art of writing, but they had

developed an elaborate system of knotted cords called quipus.

These were made of the wool of the alpaca or the llama, dyed in

various colors, the significance of which was known to the

magistrates. The cords were knotted in such a way to represent

the decimal system and were fastened at close intervals along

the principal strand of the quipus. Thus an important message

relating to the progress of crops, the amount of taxes

collected, or the advance of an enemy could be speedily sent by

the trained runners along the post roads."

�Lost City of the Incas, The Story

of Machu Picchu and its Builders� by Hiram Bingham.

Hiram Bingham at Machu Picchu, 1911

The inspiration for Indiana Jones?

|

|

|

The Quipus

and The Royal Commentaries of the Inca

In 1609, the Inca Garcilaso de la Vega published the

first volume of his Royal Commentaries of the Incas in

Lisbon. He wrote:

The

word quipu means both knot or to knot; it

was also used for accounts, because they were kept by

means of the knots tied in a number of cords of

different thicknesses and colors, each one of which had

a special significance. Thus, gold was represented by a

gold cord, silver by a white one, and fighting men by a

red cord. The

word quipu means both knot or to knot; it

was also used for accounts, because they were kept by

means of the knots tied in a number of cords of

different thicknesses and colors, each one of which had

a special significance. Thus, gold was represented by a

gold cord, silver by a white one, and fighting men by a

red cord.

When their

accounts had to do with things that have no color - such

as grain and vegetables - they were classified by

categories, and, in each category, by order of

diminishing size. Thus, to furnish an example, if they

had had to count the various types of agricultural

production in Spain, they would have started with

wheat, then rye, then peas, then beans, and so forth. In

the same way, in order to make an inventory of the arms

of the imperial army, they first counted the arms that

were considered to belong in a superior category, such

as lances, then javelins, bows and arrows, hatchets and

maces, and lastly, slings, an any other arms that were

used. In order to ascertain the number of vassals in the

Empire, they started with each village, then with each

province: the firs cord showed a census of men over

sixty, the second, those between fifty and sixty, the

third, those from forty to fifty, and so on, by decades,

down to the babes at the breast.

Occasionally

other, thinner, cords of the same color, could be seen

among one of these series, as though they represented an

exception to the rule; thus, for instance, among the

figures that concerned the men of such and such an age,

all of whom were considered to be married, the thinner

cords indicated the number of widowers of the same age,

for the year in question: because, as I explained

before, population figures, together with those of all

the other resources of the Empire, were brought up to

date every year.

According to

their position, the knots signified units, tens,

hundreds, thousands, ten thousands and, exceptionally,

hundred thousands, and they were all as well aligned on

their different cords as the figures that an accountant

sets down, column by column, in his ledger. Indeed,

those men, called quipucamayus, who were in

charge of the quipus, were exactly that, imperial

accountants.

The number

of quipucamayus scattered throughout the Empire, was

proportional to the size of each place. Thus the

smallest villages numbered four, and others twenty, or

even thirty. The Incas preferred this arrangement. even

in places where one accountant would have sufficed, the

idea being that, if several of them kept the same

accounts, there was less risk that they would make

mistakes.

Every

year, an inventory of all the Inca's possessions was

made. Nor was there a single birth or death, a single

departure or return of a soldier, in all the Empire,

that was not noted on the quipus. And indeed, it may be

said that everything that could be counted, was counted

in this way, even to battles, diplomatic missions, and

royal speeches. But since it was only possible to record

numbers in this manner, and not words, the quipucamayus

assigned to record ambassadorial missions and speeches,

learned them by heart, at the same time that they noted

down the numbers, places and dates on their quipus; and

thus, from father to son, they transmitted this

information to their successors. The speeches exchanged

between the Incas and their vassals on important

occasions, such as the surrender of a new province, were

also transmitted to posterity by the amautas, or

philosophers, who summarized them in simple, clear

fables, in order that they might be implanted by word of

mouth in the memories of all the people from those at

court to the inhabitants of the most remote hamlets. The

harauicus, or poets, also composed poems based on

diplomatic records and royal speeches. These poems were

recited for a great victory or festival, and every time

a new Inca was knighted. Every

year, an inventory of all the Inca's possessions was

made. Nor was there a single birth or death, a single

departure or return of a soldier, in all the Empire,

that was not noted on the quipus. And indeed, it may be

said that everything that could be counted, was counted

in this way, even to battles, diplomatic missions, and

royal speeches. But since it was only possible to record

numbers in this manner, and not words, the quipucamayus

assigned to record ambassadorial missions and speeches,

learned them by heart, at the same time that they noted

down the numbers, places and dates on their quipus; and

thus, from father to son, they transmitted this

information to their successors. The speeches exchanged

between the Incas and their vassals on important

occasions, such as the surrender of a new province, were

also transmitted to posterity by the amautas, or

philosophers, who summarized them in simple, clear

fables, in order that they might be implanted by word of

mouth in the memories of all the people from those at

court to the inhabitants of the most remote hamlets. The

harauicus, or poets, also composed poems based on

diplomatic records and royal speeches. These poems were

recited for a great victory or festival, and every time

a new Inca was knighted.

When the

curacas and dignitaries of a province want to know some

historical detail concerning their predecessors, they

asked these quipucamayus, who were, in other words, not

only the accountants, but also the historians of each

nation. The result was that the quipucamayus never let

their quipus out of their hands, and they kept passing

their cords and knots through their fingers so as not to

forget the tradition behind all these accounts. In fact,

their responsibility was so great and so absorbing, that

they were exempted from all tribute as well as from all

other kinds of service.

All laws,

ordinances, rites, and ceremonies throughout the Empire

were recorded by these same means.

When my

father's Indians came to town on Midsummer's Day to pay

their tribute, they brought me the quipus; and the

curacas asked my mother to take note of their stories,

for they mistrusted the Spaniards, and feared that they

would not understand them. I was able to reassure them

by re-reading what I had noted down under their

dictation, and they used to follow my reading, holding

on to their quipus, to be certain of my exactness; this

was how I succeeded in learning many things quite as

perfectly as did the Indians. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

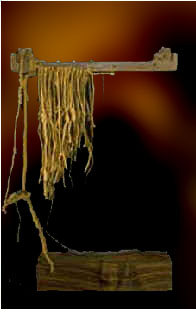

Illustrations from 1615 by

The "Indian Chronicler" Felipe Guaman

Poma de Ayala about the quipu.

Finding his most persuasive medium to be the visual image,

he organizes his 1200-page Nueva cor�nica y buen gobierno

(New Chronicle and Good Government) around his 398

pen-and-ink drawings, all skillfully executed by his own hand.

For the archaeologist, Guaman Poma's drawings of native life

under the Incas are like photographs of the past.

| |

|

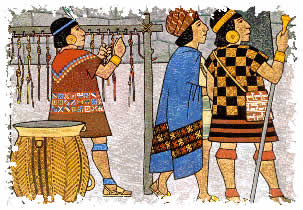

An encounter

at a "Collca" or "Warehouse of the Inca": Tupac Inca

Yupanqui (left) interviews his accountant or

warehousekeeper (right). The warehousekeeper is

extending a cord record or quipu, which contains

records of goods in the storage chambers. |

|

|

|

Chief

accountant and treasurer, authority in charge of the quipu

of the kingdom.

In the lower left corner, there is an abacus counting

device used with maize kernels on which computations

were performed and later transferred to the quipu.

The maize

kernels are the first numbers of the Fibonacci series,

in which each number is a sum of two previous: 1, 2, 3,

5. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The native

administrator of resources, with the book and quipu he uses for

accounting. |

|

|

|

The Inka�s

secretary and accountant who records the dispositions of the

royal lords. |

|

|

Reference:

Guaman Poma - 'El primer Nueva cor�nica y buen gobierno'.

|

|

|

|

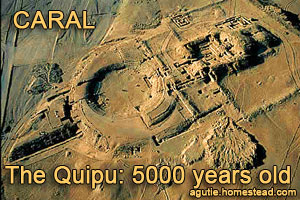

Caral: Ancient Peru city reveals 5,000-year-old

'writing'

July 19, 2005, 22:45,

SABC News

Archeologists

in Peru have found a "quipu" on the site of the oldest

city in the Americas, indicating the device, a

sophisticated arrangement of knots and strings used to

convey detailed information, was in use thousands of

years earlier than previously believed. Previously the

oldest known quipus, often associated with the Incas

whose vast South American empire was conquered by the

Spanish in the 16th century, dated from about 650 AD. Archeologists

in Peru have found a "quipu" on the site of the oldest

city in the Americas, indicating the device, a

sophisticated arrangement of knots and strings used to

convey detailed information, was in use thousands of

years earlier than previously believed. Previously the

oldest known quipus, often associated with the Incas

whose vast South American empire was conquered by the

Spanish in the 16th century, dated from about 650 AD.

But Ruth Shady, an archeologist leading investigations

into the Peruvian coastal city of Caral, said quipus

were among a treasure trove of articles discovered at

the site, which are about 5,000 years old. "This is the

oldest quipu and it shows us that this society ... also

had a system of "writing" (which) would continue down

the ages until the Inca empire and would last some 4,500

years," Shady said. She was speaking before the opening

in Lima today of an exhibition of the artifacts which

shed light on Caral, which she called one of the world's

oldest civilizations.

The quipu with its well-preserved, brown cotton strings

wound around thin sticks, was found with a series of

offerings including mysterious fiber balls of different

sizes wrapped in "nets" and pristine reed baskets. "We

are sure it corresponds to the period of Caral because

it was found in a public building," Shady said. "It was

an offering placed on a stairway when they decided to

bury this and put down a floor to build another

structure on top."

Pyramid-shaped public buildings were being built at

Caral, a planned coastal city 180km north of Lima, at

the same time that the Saqqara pyramid, the oldest in

Egypt, was going up. They were already being

revamped when Egypt's Great Pyramid of Keops (or Khufu)

was under construction, Shady said. "Man only began

living in an organized way 5,000 years ago in five

points of the globe - Mesopotamia (roughly comprising

modern Iraq and part of Syria), Egypt, India, China and

Peru," Shady said, adding Caral was 3,200 years older

than cities of another ancient American civilization,

the Maya.

|

|

|

|

Knotty

Incan Accounting Untangled

Knotty

Incan Accounting Untangled

Source: Science News, August

12, 2005

A ball of string tied

into countless knots could very well be seen as a source

of frustration. But for the ancient Inca civilization,

carefully tied knots formed the basis of a method of

record-keeping known as khipus. Now researchers report

that the ledger system is more complex than previously

believed and includes a way of communicating information

to higher-ups in the well-categorized Incan chain of

command between workers and administrators with higher

rank.

Hundreds of khipus, each consisting of a single strand

of wool from which hundreds to thousands of other

knotted strings hang, have been discovered to date. Gary

Upton and Carrie J. Brezine of Harvard University

designed a computer program to analyze the patterns in

21 khipus recovered from a site in Puruchuco, an Inca

administrative center on the coast of Peru near modern

day Lima. They discovered that certain patterns within

the strings of varying colors and lengths appear to

contain numerical data that represent summations. What

is more, the information is arranged among the khipus in

a ranked pattern with three levels of authority.

Information is passed between them by including the sum

from a khipu in one level on a khipu representing a

higher level.

|

|

|

|

Quipus of Rapaz Quipus of Rapaz

Left, A

collection of Quipus in San Cristobal de Rapaz, Oyon,

Lima-Peru.

A project of research and

conservation began in January 2004 with an agreement

between the village and the anthropologist Frank

Salomon, of the University of Wisconsin in the USA. The

village agreed to give access for scientific study in

exchange for conservation help to make the quipus and

their environment safer against deterioration.

Source:

The Khipu Patrimony of Rapaz, Peru |

|

|

|

Quipu

as a central metaphor

Quipu

as a central metaphor

In Quipu, Arthur Sze�s

eighth book of poetry, he writes with imaginative rigor

and urgency poems that move across cultures and time,

from elegy to ode, to find a precarious splendor.

Source: Quipu by Arthur Sze

Quipu was a tactile

recording device for the pre-literate Inca, an

assemblage of colored knots on cords. Sze utilizes quipu

as a central metaphor, knotting and stringing luminous

poems that each have an essential place and integrity,

each contribute to the recurrent �knotting� in the book.

Sze�s language is taut and startling, and what appears

stable may actually be volatile. In Quipu Sze harnesses

the particulars of our lives and spins them into

something enduring. He makes us envision the terrors and

marvels of our contemporary world in this collection of

crucial poems of our time.

What is �Quipu?�

Quipu means knot in Quechua, the native language of the

Andes. The Incas had a system of accounting and data

recording that relied on the quipu, a devise in which

cords of various colors were attached to a main cord

with knots. The number and position of knots as well as

the color of each cord represented information about

commercial goods and resources. Quipu-makers were

responsible for encoding and decoding the information.

The messages included information about resources in

storehouses, taxes, census information, the output of

mines, or the composition of work forces. Archeologists

have recently suggested that authors used the quipu to

compose and preserve poems and legends. Because there

were relatively few words in Quechua, the cords of a

quipu could be used as pronunciation keys.

In "The Angle of Reflection

Equals the Angle of Incidence," he writes:

Quinoa simmers in a pot;

the aroma of cilantro

on swordfish; the cusp of spring when you

lean your head on my shoulder. Orange crocuses

in the backyard form a line. Once is a scorched

site;

we stoop in the grass, finger twelve keys with

interconnected rings on a swiveling yin-yang coin,

dangle them from the gate, but no one claims them.

|

|

|

|

Conversations:

String Theorist Conversations:

String Theorist

Unraveling a knotty Inca

puzzle

Source: Archaeology, A

publication of the Archaeological Institute of America,

Volume 58 Number 6, November/December 2005 .

Khipu, the enigmatic and

still undeciphered record-keeping system of elaborately

knotted strings used by the Inca Empire, has long

intrigued anthropologist Gary Urton. Since 2002, he and

his colleague Carrie Brezine, a mathematician, have

maintained the Khipu Database Project at Harvard

University, which corrals all existing khipu scholarship

in one online repository. Most recently, they announced

they may have found the meaning of a particular sequence

of knots. ARCHAEOLOGY spoke with Gary Urton about

mystified Spanish colonials, teaching Harvard students

how to make khipu, and bringing tax records to the

afterlife.

See more.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|